History

The Road to School Desegregation in King George County

The events leading up to the integration of schools in King George County, Virginia, were a significant part of the national struggle for civil rights. Despite having unsettled the King George community while advancing the cause of both local and national black education, two pivotal court cases of historical significance (Civil Action No. 631 and Civil Acton No. 3579) are seldom remembered today. Twice within two decades, these cases represented the black community of King George and its NAACP attorneys’ legal action against the local school board for equal educational opportunities for their children..

The first legal victory, Civil Action No. 631, resulted in the opening of Ralph Bunche High School, with facilities comparable to those of the local white school. Then, with the advent of Civil Action No. 3579, the community triumphed again in 1968 with the full integration of the King George County school system.

Today, the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association advocates for transforming the former school building into a vibrant venue to accommodate a museum gallery, meeting spaces and more. This venue would also help address the community’s existing social needs and memorialize the school’s historical significance.

Separate But (Not) Equal

In 1896, in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment granted political but not social equality to black citizens. As such, the justices legitimized the doctrine of “separate but equal,” which held that racially segregated facilities did not breach the Constitution as long as they were equal.This decision enabled the passage of extensive discriminatory laws that relegated blacks to second-class citizenship.

Named after a black character in minstrel shows, Jim Crow laws mandated the establishment of separate accommodations for blacks, usually of inferior quality to those for whites. The racial order was manifested in the “White Only” and “Colored” signs in buses, trains, restaurants, restrooms, theaters and most public spaces across the South.

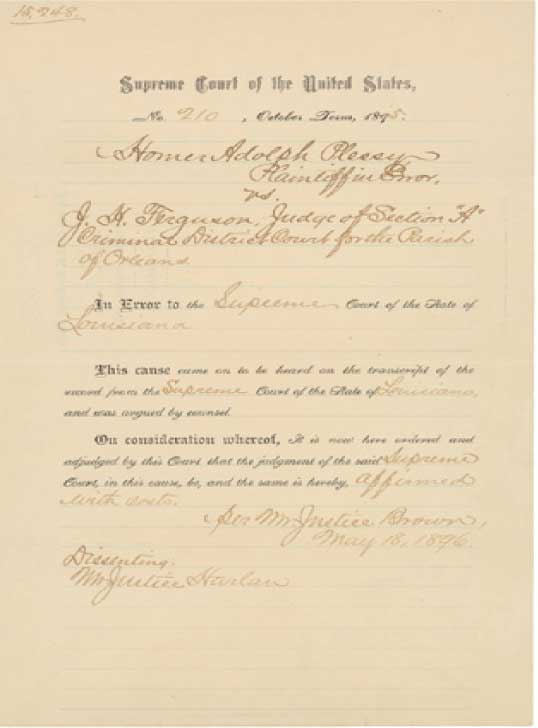

Judgement in Plessy v. Ferguson

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

In 1892 Homer Plessy, a black man, refused to move from a whites-only train car of the East Louisiana Railroad. After Plessy’s arrest for civil disobedience, his lawyer argued that the racial segregation of cars violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. With only one dissenting vote, on May 18, 1896, in the landmark case Plessy v. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “separate but equal” segregation was constitutional.

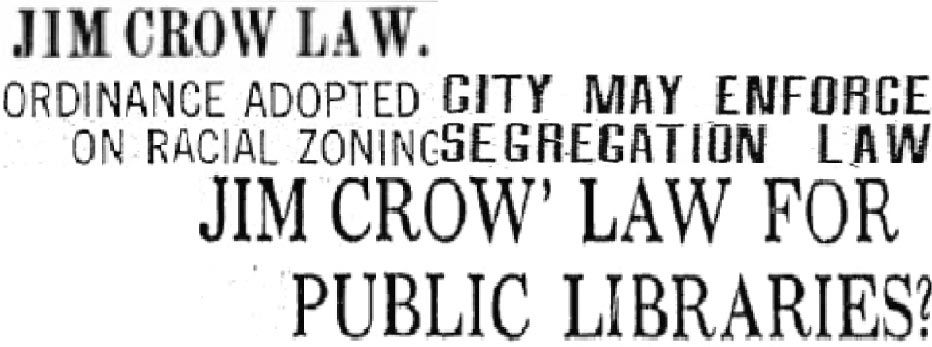

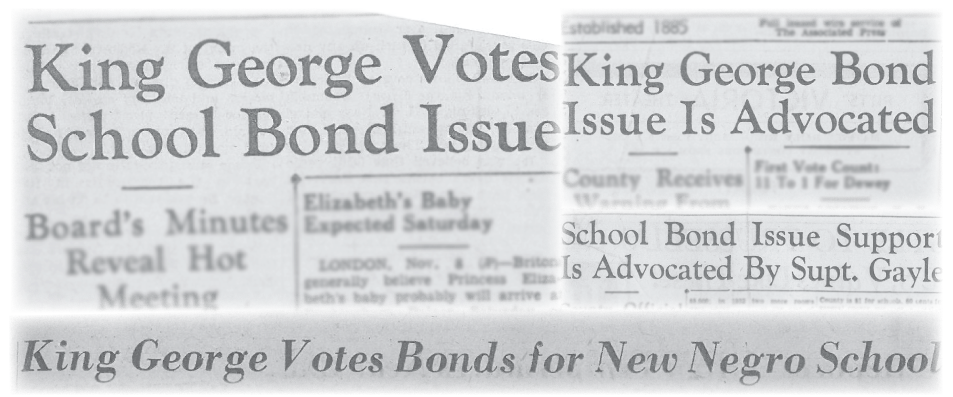

Newspaper Headlines

Courtesy of the Daily Oklahoman

Newspapers reported on Jim Crow laws at national, state and city levels, each having its specific and sometimes overlapping, priorities. National attention focused mainly on interstate transportation. Segregation of transportation and public education as well as the regulation of interracial marriage were state-level concerns. Local segregationists’ interests stretched from libraries, hospitals and poolrooms to cemeteries and school for blinds.

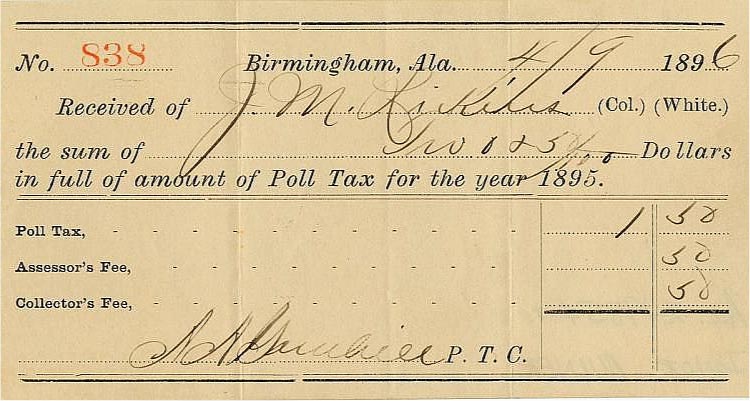

Poll Tax Receipt

Courtesy of the Division of Political History, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

During the 1890s, white lawmakers began curtailing African Americans’ voting rights as well. New disenfranchisement laws circumvented the Fifteenth Amendment’s prohibition of racial discrimination against voters. Such tactics included the Grandfather Clause, literacy tests and poll taxes. A poll tax receipt like this one from Alabama served as an admission ticket to the polling place.

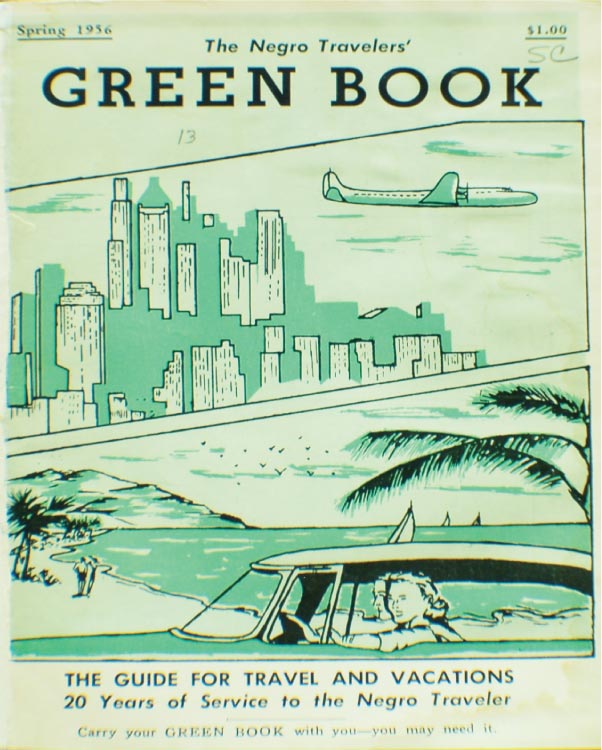

The Green Book

A product of the late Jim Crow Era, The Negro Travelers’ Green Book promised black travelers an “embarrassment-free” experience. This guide provided state-by-state listings of hotels, restaurants, movie theaters, doctors and other businesses that welcomed black patrons. Defeating the users’ expectations at times, the guide led tourists to segregated accommodations.

A Sign at the Greyhound Bus Station in Rome, Georgia

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

A Rest Stop for Greyhound Passengers

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

As tools of Jim Crow laws, segregation signs directed blacks to their own “separate but equal” facilities. In reality, these signs prohibited African Americans’ access to white-operated beauty parlors, swimming pools, restaurants, stores, hotels and other public accommodations. At the same time, because numerous black communities lacked such resources, residents simply did without them or traveled far to attend black-owned ones.

The NAACP Strategy: Advancement Through Education

Founded in 1909 to fight against the segregation and discrimination of black people, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) led the legal attack against “separate but equal” facilities. Spearheading these efforts was a new generation of lawyers formed under the mentorship of Charles H. Houston at Howard University Law School. Beginning in the 1930s, they designed a long-term strategy for undermining the “separate but equal” doctrine. Their plan aimed first at challenging the education system and forcing states to create equal facilities for black students. With the legal precedent set, the next goal would be full school integration along with the overturn of the Plessy v. Ferguson decision.

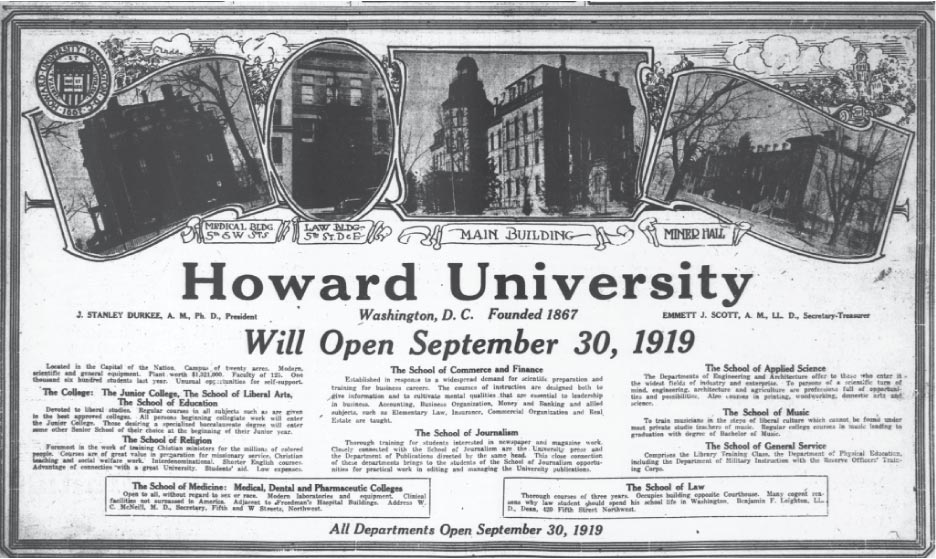

Howard University Advertisement

The Washington Times

Howard University started in 1867 as a school for black clergymen and quickly became a renowned institution of higher learning for black students. At a time when most African American schools offered only vocational training, Howard University provided degrees in education, journalism, medicine, law, commerce, music and other disciplines. Numerous prominent leaders of the Civil Rights Movement were Howard alumni.

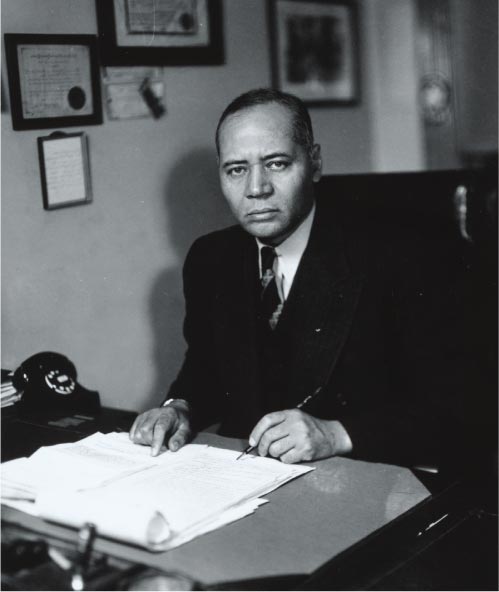

Charles H. Houston

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Charles H. Houston was the architect of the Civil Rights Movement. A professor at Howard Law School, he mentored a new generation of lawyers, whose systematic efforts undermined the legal principles of segregation. Houston believed that lawyers were “social engineers” who understood the Constitution and knew “how to explore its uses in the solving of problems of local communities and in bettering conditions of the underprivileged citizens.”

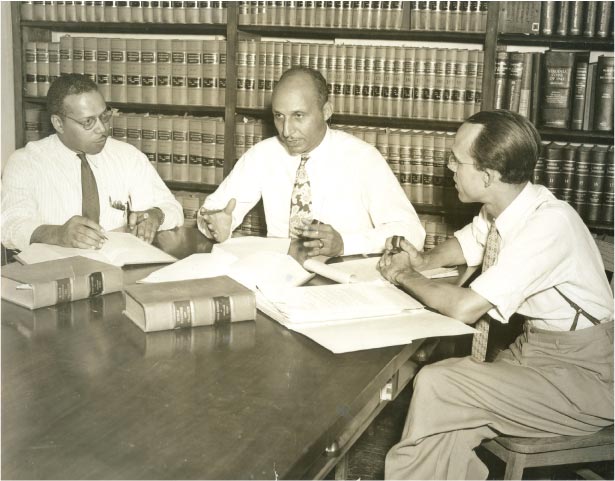

Hill, Martin and Robinson

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives

In the early 1940s, Oliver W. Hill (middle), Martin A. Martin (left) and Spottswood W. Robinson III (right) partnered in the Hill, Martin and Robinson law firm in Richmond. Together, they became the leading national experts in school inequality suits. As NAACP members, they would work with local PTA organizations on identifying black schools to provide the basis for suits as well as potential plaintiffs. Most of their early cases led to salary equalization for black teachers and equal school facilities for black students.

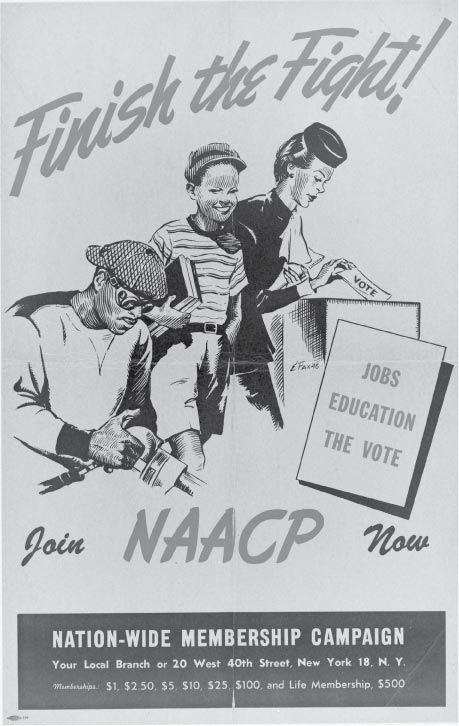

NAACP Poster

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The end of World War II energized the NAACP’s efforts to end segregation. As black soldiers returned home to find that their service did not earn their equality, they joined the NAACP in large numbers. The desegregation of the armed forces in 1948 solidified even more the stage for starting the Civil Rights Movement. Contemporary NAACP posters called black citizens to unite and “finish the fight” for equal rights.

Thurgood Marshall

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

A Howard Law School graduate, Thurgood Marshall succeeded his mentor, Charles H. Houston, as the head lawyer for the NAACP. In 1940 he established the organization’s Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDEF) to offer legal assistance to impoverished black citizens and communities. While LDEF soon became the legal arm of the Civil Rights Movement, Marshall tirelessly counseled its attorneys and oversaw numerous cases personally. In 1967, he became the first African American justice of the Supreme Court.

Demand for Change

While the Plessy v. Ferguson decision created the “separate but equal” doctrine, the equality of public facilities, including schools, was seldom achieved. As the NAACP lawyers began challenging this inequity in courts, a few residents of King George County courageously sued the local school board in 1946. The premise of Civil Action #631 was inferior “construction, equipment and facilities, instructional personnel, libraries and transportation service,” in black schools compared to their white counterparts. Civil rights attorneys Oliver W. Hill, Martin A. Martin and Spotswood W. Robinson III of Richmond, Virginia masterfully won the litigation despite the King George School Board’s fierce opposition. In July 1948, U.S. District Judge Sterling Hutchinson determined that “the defendants have unlawfully discriminated … against Negro school children.” This decision led to the opening of Ralph Bunche High School on September 2, 1949.

Lambs Creek School

Courtesy of King George County Historical Society

King George residents still remember Lambs Creek School on White Hall Road as one of the several one-room black schools in the county. All grades shared the same space and competed for the attention of just one teacher. Older boys would fuel wood-burning stoves and carry buckets of water from outside wells. Desks and supplies never sufficed and books were always hand-me-downs.

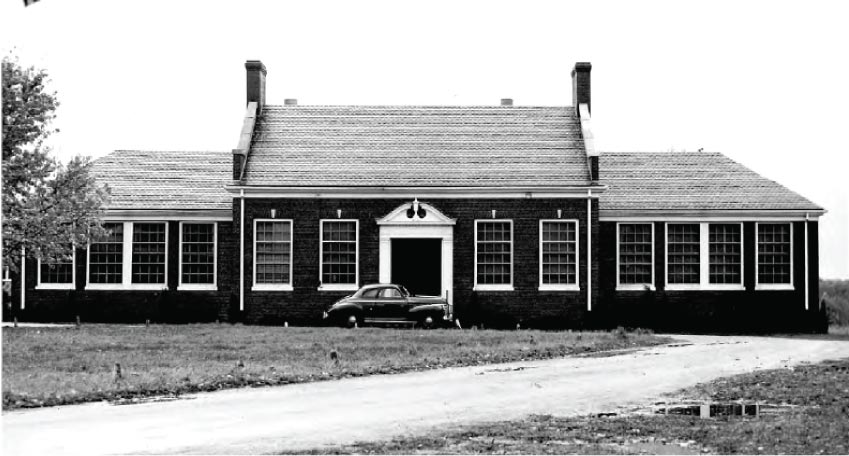

King George High School

Courtesy of the National Archives at Philadelphia

Court documents indicate that the value of local whites’ school buildings and sites, including the King George County High School shown here, was $236,000 in 1944. At the same time, the worth of blacks’ school properties amounted to $18,000. Estimated at $12,000, whites’ school furniture and equipment was valued at four times that of their black counterparts. The black high school was not accredited and black teachers earned about 25% less than their white colleagues.

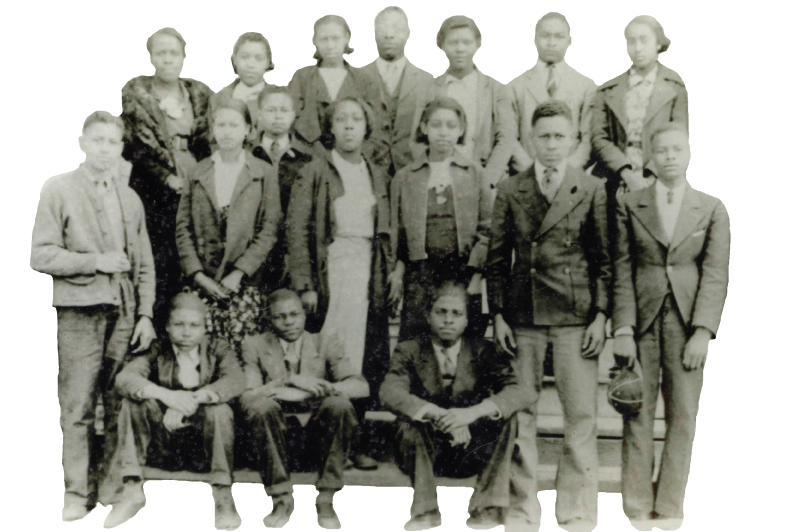

Edgehill Training School Class of 1939

Courtesy of the King George County Historical Society

The original Edgehill Training School consisted of four clapboard buildings. In the mid-1930s, buildings for grades eight through eleven were added, making it the first African American high school in King George County, Virginia. Nevertheless, Edgehill Training School was disqualified and not accredited by the State Board of Education because it did not have a twelfth grade. Other inadequacies of this school, as compared to the King George High School, were the focus of the complaints in Civil Action No.631 which led to the construction of Ralph Bunche High School in 1949 on the same site.

Oliver W. Hill

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives

“…opportunities for Negroes to become trained in anything above the level of manual labor was restricted or eliminated.”

T. Benton Gayle

Courtesy of the King George County Historical Society

In 1946, Margaret Smith and the other King George County plaintiffs in Civil Action #631 filed suit against the local school board and its longtime superintendent T. Benton Gayle. In trial testimonies and press interviews, he frequently cited existing laws and the Virginia Constitution to rationalize the segregated school system. However, statements such as “buildings alone do not make up an effective school” speak of his personal feelings towards the cause of equality.

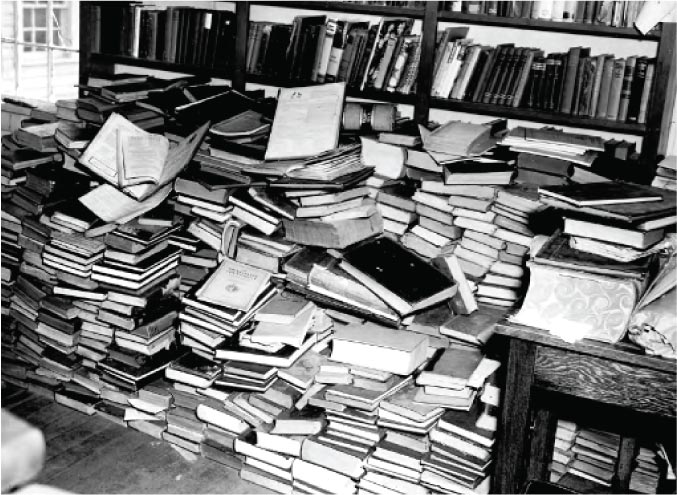

“Improved” Library at King George Training School

Courtesy of the National Archives at Philadelphia

In July 1948, Civil Action #631 concluded with the Federal District Court ordering the school board to equalize black and white school facilities. The board’s measures were meager, to say the least, under the pretext that the time left until the beginning of the school year was too short. One such action consisted of “improving” the King George Training School library with used books on inappropriate topics or in foreign languages.

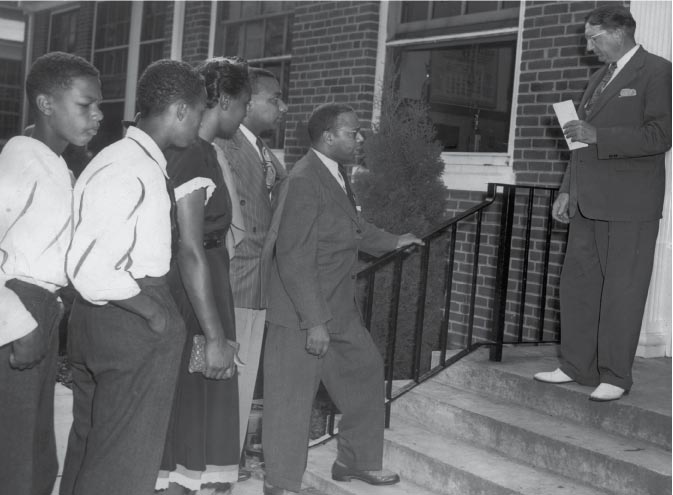

Black Students Try to Enroll at King George High School

Courtesy of the Richmond Times-Dispatch

In September 1948, after the school board failed to equalize black and white school facilities, black students’ lawyers continued to press for change. Assisted by attorney Martin A. Martin and NAACP State Secretary Lester Banks, twelve black students sought admittance to the white King George High School. After reading section 140 of the Virginia Constitution which stated, “white and black students should not be taught in the same school,” Superintendent Gayle denied the students admission.

Bond Referendum

Courtesy of The Free Lance-Star and The King George News

Black resistance to the board’s avoidance of real school equalization and fears of potential requests for the actual integration of schools led county authorities to a new plan. King George County residents were called to vote on a bond issue for the construction of a new high school for black students. On November 7, 1948 the measure passed by a 322-245 margin. Ralph Bunche High School opened less than a year later.

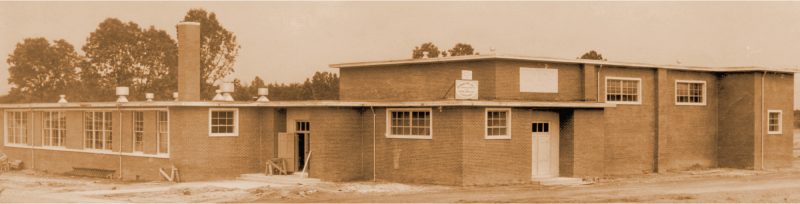

Class in Session: Ralph Bunche High School

The 1948 court order that restrained the school board of King George County from discriminating against black children heralded a new era for local African American education. Funded through a $150,000 bond voted by county residents, Ralph Bunche High School opened in September 1949. A far cry from the existing King George Training School, the new building featured multiple classrooms, a library, a gymnasium and other amenities, including a heating system and indoor bathrooms. A staff of college-trained teachers, books and a curriculum equal to that of the local white high school allowed a new generation of black students to earn accredited diplomas. Ralph Bunche High School soon became a focal point for the local African American community.

Ralph J. Bunche

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, LC-USZ62-109113

The first accredited black high school in King George County took the name of diplomat Ralph J. Bunche. A Howard University graduate, Bunche achieved international fame for his successful armistice negotiation that ended the Arab-Israeli War in 1947. By winning the Nobel Peace Prize three years later, he became the first African American recipient in the history of the award. Bunche’s motto “segregation and democracy are incompatible” drove his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement.

Photograph of Ralph Bunche High School

Courtesy of the Richmond Times-Dispatch

Ralph Bunche High School started as an accredited institution that, like its white counterpart, included grades 8 through 12. The new building shared the same location with the former King George Training School, which, after renovation, became Ralph Bunche Elementary School. The curriculum expanded with courses in sciences, arts, foreign languages and business.

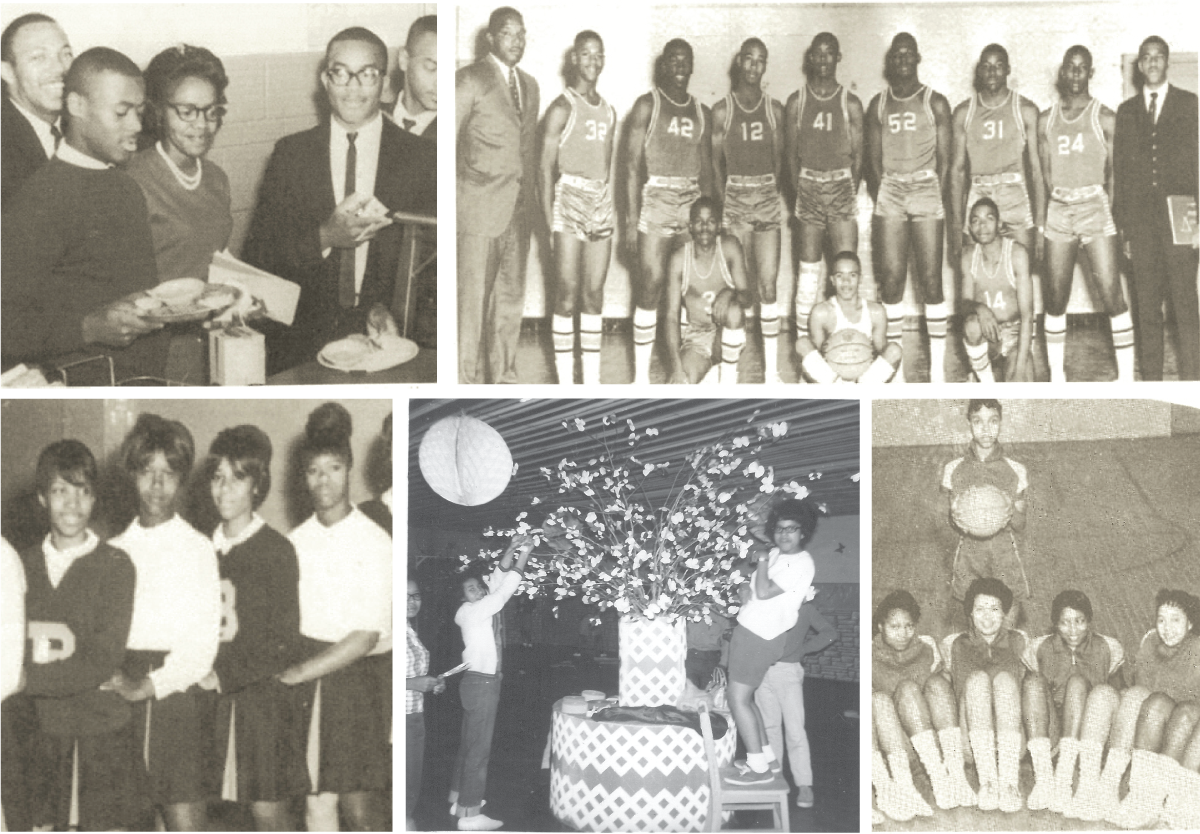

Ralph Bunche Students

Courtesy of The Free Lance-Star and The King George News

Ralph Bunche High School accomplished more than just classroom education. Apart from the rigorous academic curriculum, students enjoyed a variety of extracurricular activities from sports and theater to music and self-government programs. Teachers, students and parents came together for school events, bonding with each other and strengthening the black community of King George County. Today, most alumni name Ralph Bunche High School, along with their church and family, as the three main factors that shaped their upbringing.

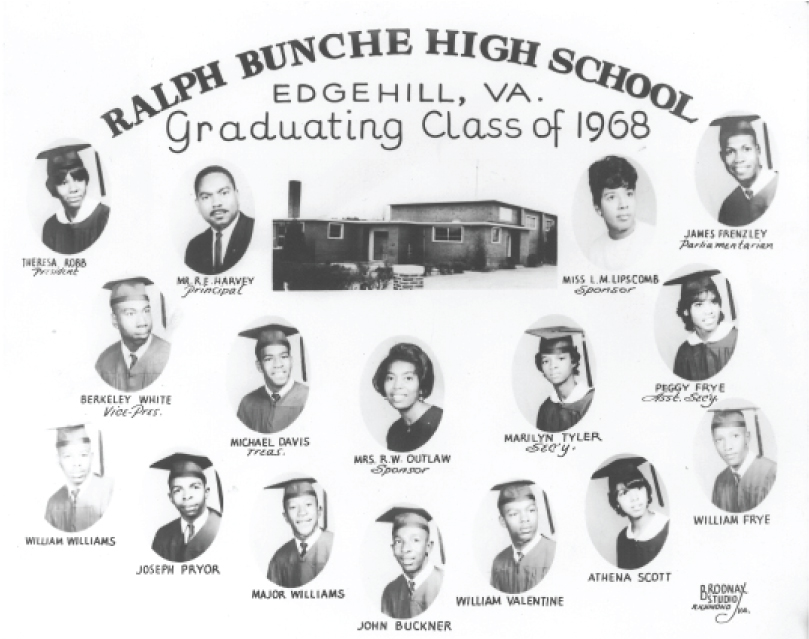

Photo of Last Graduating Class

The fourteen proud, smiling faces in this 1968 yearbook represent the last class to graduate from Ralph Bunche High School. Many alumni continued their education, receiving undergraduate and graduate degrees and embarking on impressive careers in business, social work, the military and education. Their high-school diplomas were the passport to a new world of opportunities that had seemed unattainable to their parents and grandparents.

Class Motto: “They conquer who believe they can.”

Integration or Bust!

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared school segregation unconstitutional. A year later, the Court mandated that public schools integrate “with all deliberate speed,” allowing school districts to proceed at their own pace. The decision’s ambiguous language gave opponents of desegregation the grounds to avoid compliance with the law. The state of Virginia adopted a “massive resistance” strategy that perpetuated school segregation for a few more years. In 1964, thirty-eight black students in King George County sued the School Board once again (Civil Action 3579), demanding full school integration. Following this case as well as the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the King George Consolidated High School opened to students of all races in 1968.

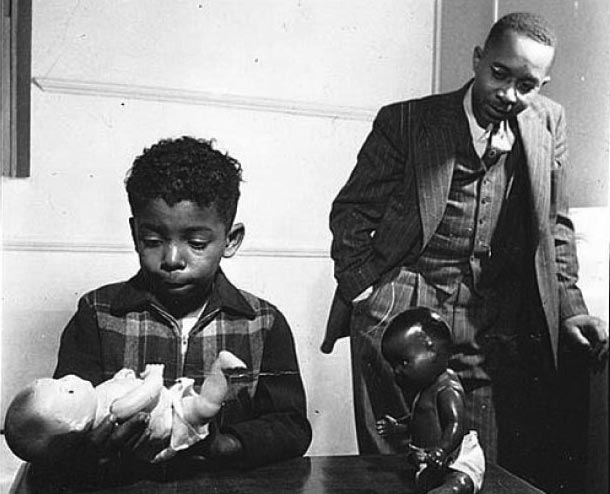

The Doll Test

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The strategy of plaintiffs’ lawyers in Brown v. Board of Education relied on evidence presented to the court by psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark. Their “doll test” involved black children between the ages of three and seven who were shown plastic dolls identical in every aspect except for their color. Most of the subjects attributed positive characteristics to the white dolls, thus allowing the Clarks to conclude that “prejudice, discrimination and segregation” had a negative psychological impact on black children.

Line in Front of the Supreme Court

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

On December 7, 1953, large crowds of African Americans gathered outside the Supreme Court to hear the second round of arguments for Brown v. Board of Education. Limited public seating led to long lines that wrapped around the block. The case grabbed the nation’s attention and it was well understood that the court’s decision would be monumental, no matter the outcome.

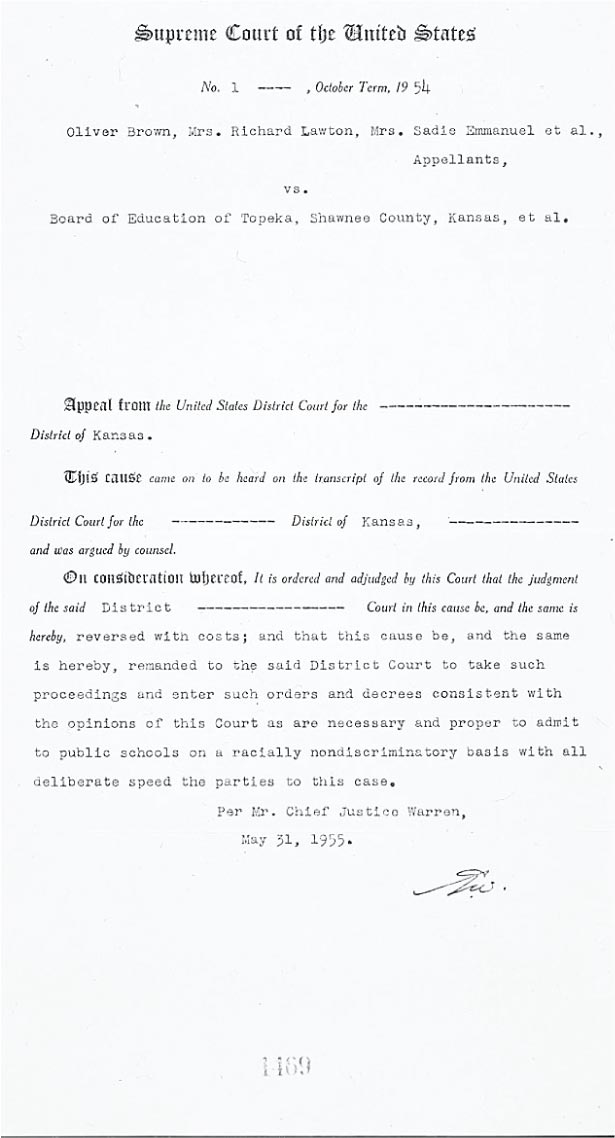

Brown v. Board of Education Final Decision

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

In 1952, the Supreme Court began hearings on several cases on school desegregation in Kansas, Virginia, Delaware, South Carolina and the District of Columbia. Consolidated under the name Brown v. Board of Education, these cases gave the NAACP lawyers the foundation for the final attack on segregation. Their legal, historical and psychological evidence led to a favorable judgment on behalf of the plaintiffs. At the end of the deliberations, Chief Justice Earl Warren announced, “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Woman Protesting in Fredericksburg, Virginia

Courtesy of the Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center

The “deliberate speed” mentioned in the Brown v. Board of Education decision gave white supremacists the grounds to resist integration and sparked a mass movement to end racism in all aspects of life. Sit-ins, boycotts, marches and other forms of nonviolent resistance became the new strategy of African American leaders. Despite creating crises, it enabled the dialogue between activists and officials and gradually strengthened the former’s positions. This photo shows Jerene Mercer, a protester in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

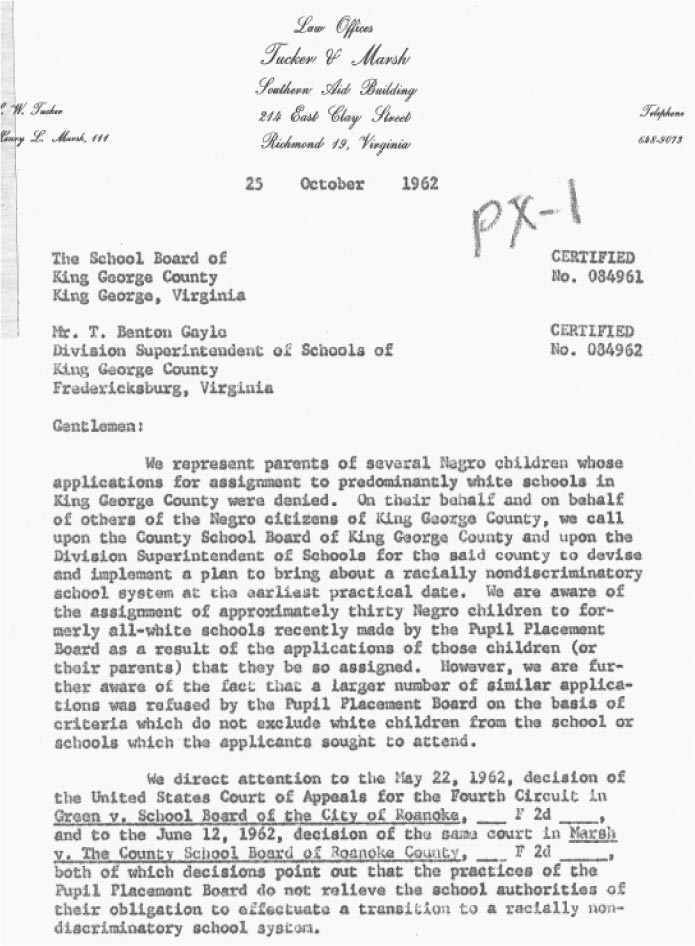

Preamble to Civil Action #3579

Courtesy of the National Archives at Philadelphia

Virginia’s massive resistance to the Brown v. Board of Education decision energized the black community in King George County once again. This 1962 letter addressed to Superintendent T. Benton Gayle and the local school board preceded Civil Action #3579. Thirty-eight plaintiffs attacked the “freedom of choice” plan, which granted black students the right to request enrollment in white schools but also gave pupil placement boards room to use selection criteria that disguised racial segregation. A year later, the judge restrained the defendants from using racially discriminatory criteria in the assignment of pupils to public schools.

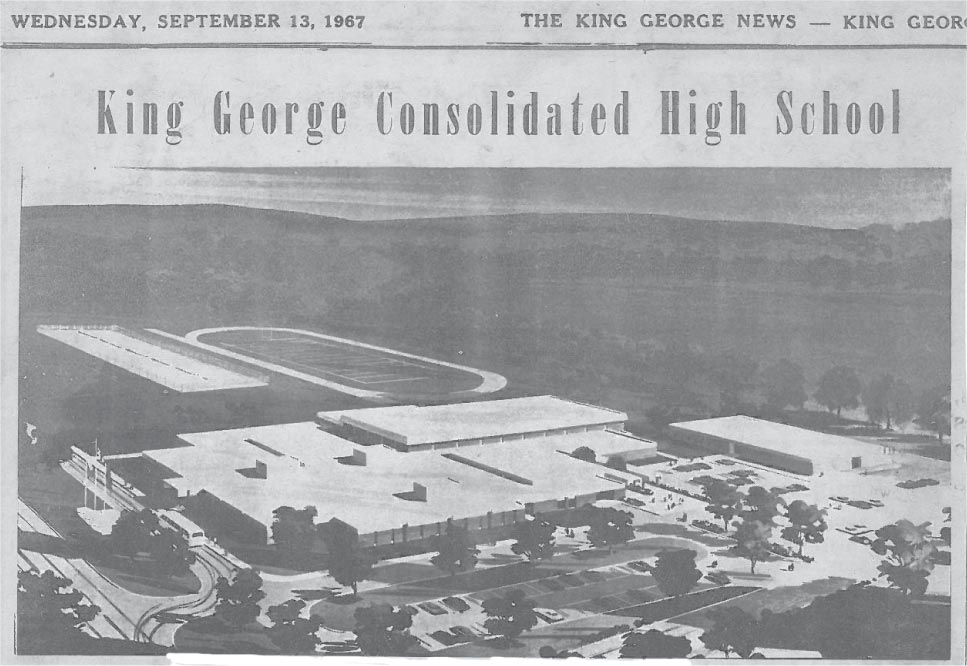

King George Consolidated High School

Courtesy of The King George News

In September 1967, The King George News referred to the planned King George Consolidated High School as being “representative of new schools being built in the Old Dominion.” The facility boasted air conditioning, flexible classrooms, closed-circuit television and a gym and auditorium, which doubled as after-hours meeting spaces. For the first time in the history of the county, black and white students would share real equal education.

The Continuing Journey

As King George High School opened to black and white students in 1968, the Ralph Bunche High School building began a slow and steady decline as it housed housed administrative offices and storage spaces before closing down completely. Prolonged neglect and decay fueled talks in the late 1990s on the building’s demolition. These prospects energized the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association, which succeeded in adding the building to the National Register of Historic Places in 2006. Today, RBAA, with the support of the King George County Board of Supervisors, local residents and businesses could transform the former Ralph Bunche High School into a public venue with a museum, gallery, exhibition spaces, offices and meeting rooms. This would recognize and uphold the building’s historic significance as a symbol of the struggle for justice and equality.

Ralph Bunche Alumni Association

Between 1949 and 1968, nineteen senior classes graduated from Ralph Bunche High School. RBAA includes alumni, friends, community members, organizations and businesses and welcomes everyone committed to the school’s restoration and preservation as well as its educational and historical legacy. In 2004, the Historic Preservation of Ralph Bunche School Proclamation rallied the alumni community behind the cause of bringing “recognition to the educational and historical significance” of the school.

Alumni Association Members

Officers and members, past and present, have worked diligently to diversify the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association’s portfolio of activities. Initiatives such as the academic scholarship award and the annual cookout have become highly regarded traditions. Dinner dances, galas, cruises and group participation at local events have served to bond members. However, all undertakings support the Association’s ultimate goal of raising public awareness of the school’s preservation needs.

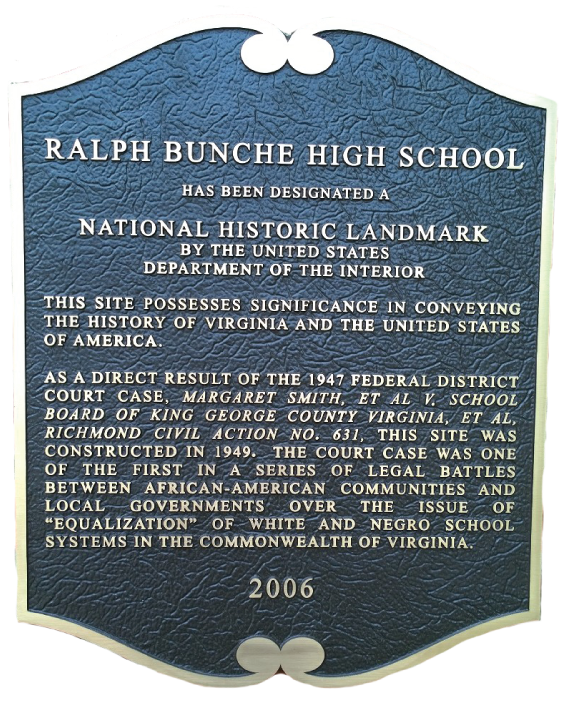

National Historic Landmark Designation

King George has many properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Among these, Ralph Bunche High School was the first twentieth-century structure directly related to the history of the local African American community.

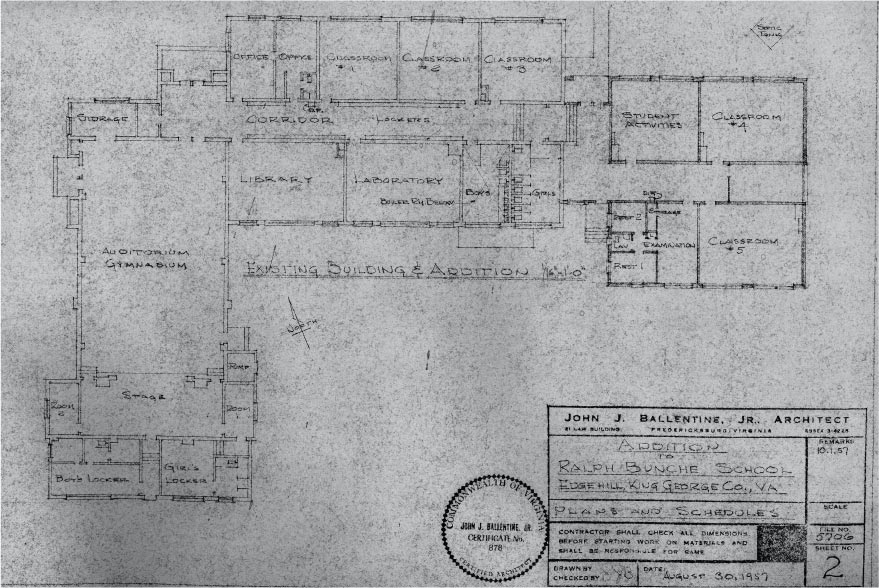

Ralph Bunche High School Blueprint

The building of Ralph Bunche High School features the work of two architects. Samuel N. Mayo planned the original 1949 structure and John J. Ballentine Jr. was responsible for the 1957 addition, which included classrooms, a kitchen and a cafeteria. Ballentine’s drawings serve as a reminder of the generous existing space that, if renovated, can successfully meet the demands of a vibrant venue.

Two Former Schools Functioning as Community Centers

Courtesy of John J. Wright Educational and Cultural Center and A.T. Johnson Museum

The conversion of schools into community centers is a business model that has been successfully applied elsewhere in Virginia. The John J. Wright Educational and Cultural Center in Spotsylvania County, Virginia functions in the building of the former John J. Wright Consolidated School. It houses a museum and a library while also offering educational services to pre-K-12 students in Spotsylvania County. The former Armstead Tasker Johnson High School in Montross opened in 2007 as a museum and space for community meetings.

Watch The Road to School Desegregation Documentary

Produced by the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association and King George County School Board, The Road to School Desegregation is a documentary video detailing the struggle for educational equality in King George County, Virginia and across the United States. Deepen your knowledge of this part of our nation’s vital history and support the mission of the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association in the process!

TAKE ACTION

Your contributions and involvement with the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association directly fund historic preservation, community education and the college scholarship award. Find out more about how you can get involved and make an important difference.

Credits

This exhibition was produced at the request of the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association in King George, Virginia by the students enrolled in the Museum Design and Interpretation Laboratory at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia during the spring semester of 2015.

Students

Erin Clark, Theresa Cramer, Rebecca Hoehn, Julia Jin, Gil Kenner, Gabrielle Lindemann, Sarah Longenderfer, Margaret Lovitt, Paul Murphy, Dana Nordling, Kara Saffos

Professor

Dr. Cristina Turdean