News

Exhibit Details Ralph Bunche High School’s Role in School Desegregation Movement

There was an interesting dynamic in Dahlgren this week at the unveiling of an exhibit that describes school desegregation in King George County.

The auditorium of the University of Mary Washington’s Dahlgren campus was packed with more than 150 people. Dozens wore orange and blue ribbons, colors of their alma mater, Ralph Bunche High School.

Many of them had lived through the history spelled out in the exhibit, “The Road to School Desegregation in King George County.”

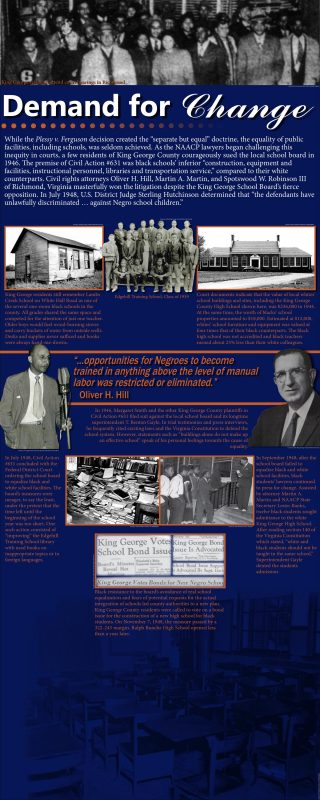

Some were among 13 students and nine adults who sued the School Board in 1946 for the right to have a facility of their own. Their action led to the 1949 opening of the all-black Ralph Bunche school.

“This brings back a lot of memories,” said Barbara Howard Ashton, a member of the school’s first graduating class in 1950. “It makes you feel so good.”

Others were among 70 plaintiffs in a 1962 court case that eventually led to integration of county schools six years later.

In front of the audience and next to the panels sat fresh-faced students from UMW. They weren’t even born when blacks attended second-class facilities and used materials and books handed down from white schools.

But because the students had researched Ralph Bunche—and the national climate during segregation—to put the panels together, they understood the courage of “people who stuck their necks out,” said UMW student Dana Nordling.

“We were impressed and moved by the sacrifices people had to go through,” said student Theresa Cramer.

Those who took their quest for an equal education to court did so at risk to their jobs and families and with no guarantee of success, she said. Cramer also noted that nothing happened overnight.

“It took a community 23 years to achieve the results,” she said.

Cramer’s teacher, UMW professor Cristina Turdean, hoped the students’ efforts to bring back to life the memories of the past would aid in the future of the former school.

“Their sacrifices should fuel your determination to do what’s needed to restore the Ralph Bunche High School,” Turdean said.

At those words, the audience stood and applauded. Nadine Lucas, chairwoman of the Ralph Bunche Advisory Committee, went to the podium, but couldn’t hold back the tears.

“Words can’t express my gratitude and how I feel today,” she said.

The struggle to get to the point that Ralph Bunche’s history is pictured on vinyl panels has taken almost as long as integration itself.

The school closed in 1968 and the association started asking in 1997 for something to be done with the aging building, before it fell into disrepair. That has already happened and the county has spent about $126,000 on piecemeal repairs.

In 2012, county supervisors approved a charter for the advisory group and tasked them with developing a plan for the building. The group also is supposed to determine what renovation is needed and where the money might come from.

The partnership between the UMW students, who are part of the Museum Design and Interpretation class and Ralph Bunche alumni came about last year. Lucas had seen a newspaper story about a similar effort involving the college students—many of whom are majoring in historic preservation and museum studies—and asked Turdean if the class would take on the Ralph Bunche project.

Turdean explained during the presentation on Tuesday the work involved. Students read books and newspaper articles that described the broader story of segregation throughout the country. Then students interviewed 13 students from Ralph Bunche to put the local context into the national perspective.

“This has been more or less putting the history of Ralph Bunche on the map again,” said Otis Penn, one of those interviewed.

Panel 1: The Road to School Desegregation in King George County

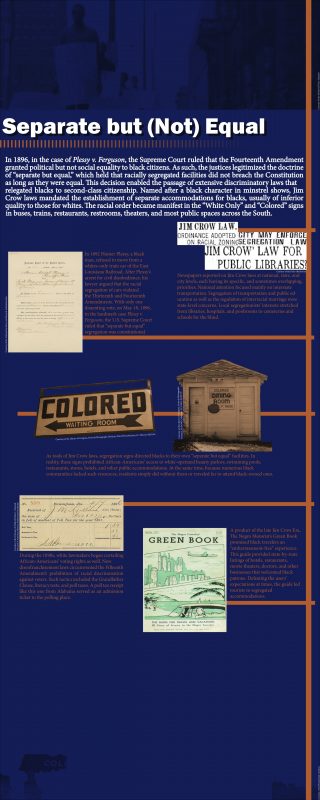

Panel 2: Separate but (Not) Equal

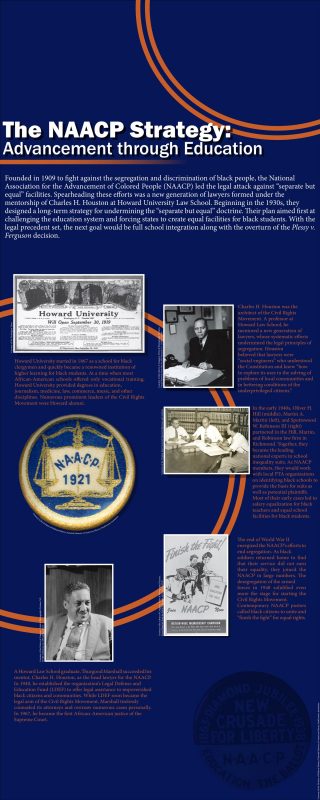

Panel 3: The NAACP Strategy

Panel 4: Demand for Change

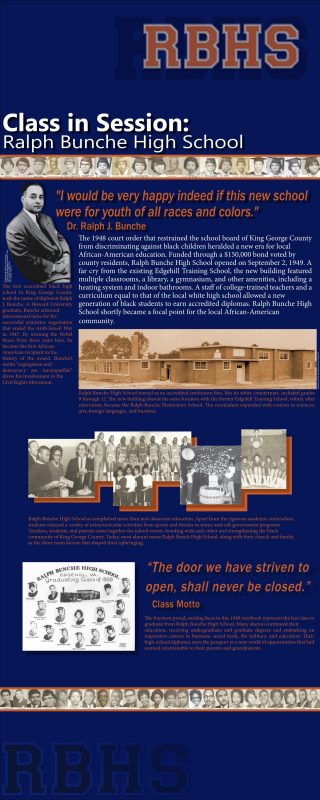

Panel 5: Class In Session

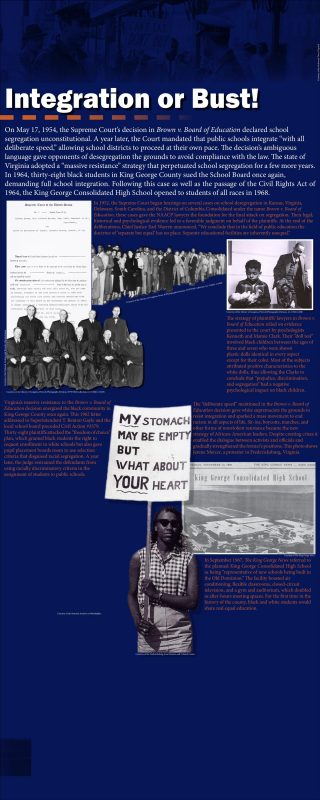

Panel 6: Integration or Bust

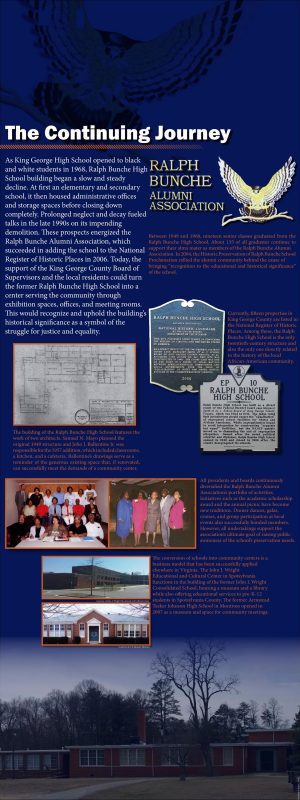

Panel 7: The Continuing Journey

Panel 8: Credits

As Lucas has said in past meetings with the King George Board of Supervisors, Ralph Bunche was “a test case in the upper South.” It was built as a result of the 1946 lawsuit under the concept of “separate but equal.” Other Ralph Bunche alumni pointed out the approach was in name only and that black schools never had the same resources and amenities as white schools.

The advisory group plans to press ahead with plans to renovate the school into a museum that would serve three purposes. It would provide historical information and resources related to the integration of public schools; serve as a place for community events, such as receptions and recitals; and host community meetings.

Claudette Jordon, president of the alumni association, reminded the audience that the group—and its fundraising campaign—isn’t for graduates of the school only.

“It’s for anyone who wants to champion the cause of refurbishing this building,” she said.

Watch The Road to School Desegregation Documentary

Produced by the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association and King George County School Board, The Road to School Desegregation is a documentary video detailing the struggle for educational equality in King George County, Virginia and across the United States. Deepen your knowledge of this part of our nation’s vital history and support the mission of the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association in the process!

TAKE ACTION

Your contributions and involvement with the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association directly fund historic preservation, community education and the college scholarship award. Find out more about how you can get involved and make an important difference.